During 1966, photographer Nurit Wilde, “Sweet Nurit from Lookout Mountain Street,” touted Jackson Browne songs to Fairfax High School teenagers in West Hollywood and Laurel Canyon.

In 1967 Wilde took the first portrait pictures of Browne. One session was done at the Orange Julius stand on Santa Monica Blvd. in West Hollywood and another at the home of Laurel Canyon-based talent manager and music industry mensch Billy James, who always championed Browne’s songs. As a 16-year-old, Browne attended the ’67 Monterey International Pop Festival. Two of Nurit’s photos are displayed in my 2008 book Canyon of Dreams The Magic and the Music of Laurel Canyon.

Browne eventually secured a publishing deal with Nina Music/Elektra Records, who placed his tunes on LPs by Joan Baez, Tom Rush and Steve Noonan. Nico and the Byrds also cut his songs.

Multi-instrumentalist Chris Darrow first encountered Browne during 1966-1968 when Darrow was a founding member of Kaleidoscope and then joined the Nitty Gritty Dirt Band.

“Jackson would show up at our gigs. Always the singer-songwriter, he set himself apart from his contemporaries at the time,” recalled Darrow in a 2008 interview we did.

“His boyish good looks and his ability to write lyrics that were beyond his age gave him an identity all his own. He had both memorable lyrics and hooks that made his music stand out against the more sensitive singer/songwriters of the time, who tended to be more introspective and insular,” underscored Darrow. “The great singer-songwriters, from Dylan to James Taylor to Leonard Cohen, all have the ability to write personally in a way that makes their words seem to speak to everyman. Browne’s second album was called For Everyman, and he became, along with the aforementioned, the front man for the singer-songwriter movement in California in the 1970s.”

Musician and photographer Henry Diltz further praised Browne to me in the late '60s after Diltz was the set photographer for the second season of The Monkees television series. My mother Hilda worked for Raybert Productions who produced The Monkees series at the Columbia-Screen Gems studios at Gower Gulch. Henry and I have fond memories of Frank Zappa, Godfrey Cambridge, Julie Newmar, Rupert Crosse, and Tim Buckley, an early influential singer-songwriter on Browne, taping episodes.

I first heard and met Browne at Doug Weston’s Troubadour club in West Hollywood and McCabe’s Guitar Shop in Santa Monica around 1970 and just a bit later around 1971. Browne had a studio apartment in the Echo Park/East Hollywood area.

"I first knew Jackson Browne when he lived around the Hollywood Bowl,” remembered Diltz in a 2008 interview we did. “Gary Burden, my partner and graphic artist, and I were hired by David Geffen to go over to this young songwriter's house and take some pictures of him around March 1971. "We had a beer and talked for a few minutes. Jackson said, 'You want to hear some of the music?’ And he went in the living room and he sat down at a grand piano and played a chord. ‘Holy shit!’ Being a musician I loved the music and was enthralled by it.

“He sat down there and played ‘Rock Me on the Water.’ Blew my mind. My jaw dropped. I got chicken skin. Goose bumps,” confessed Diltz.

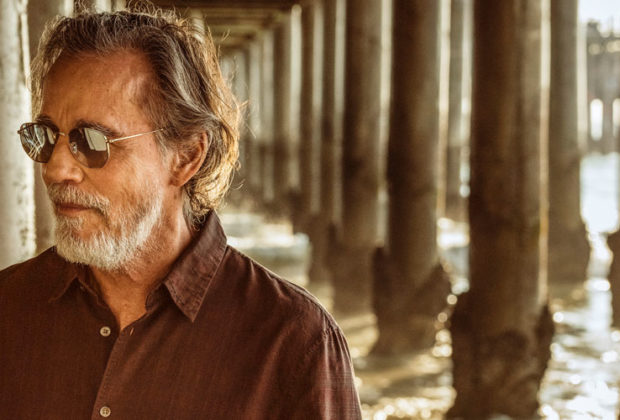

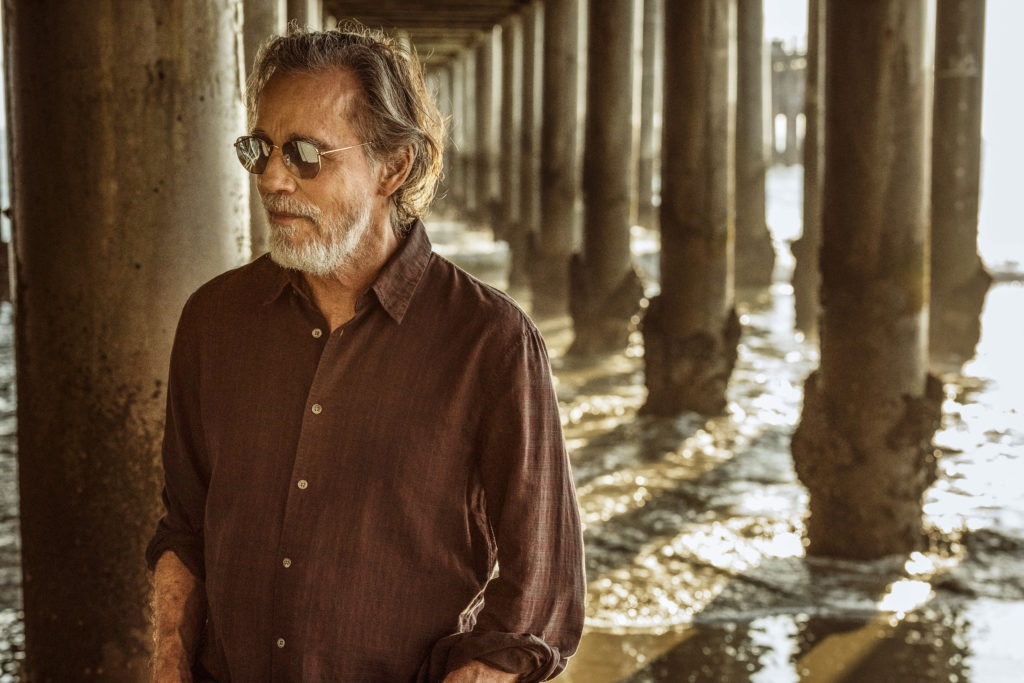

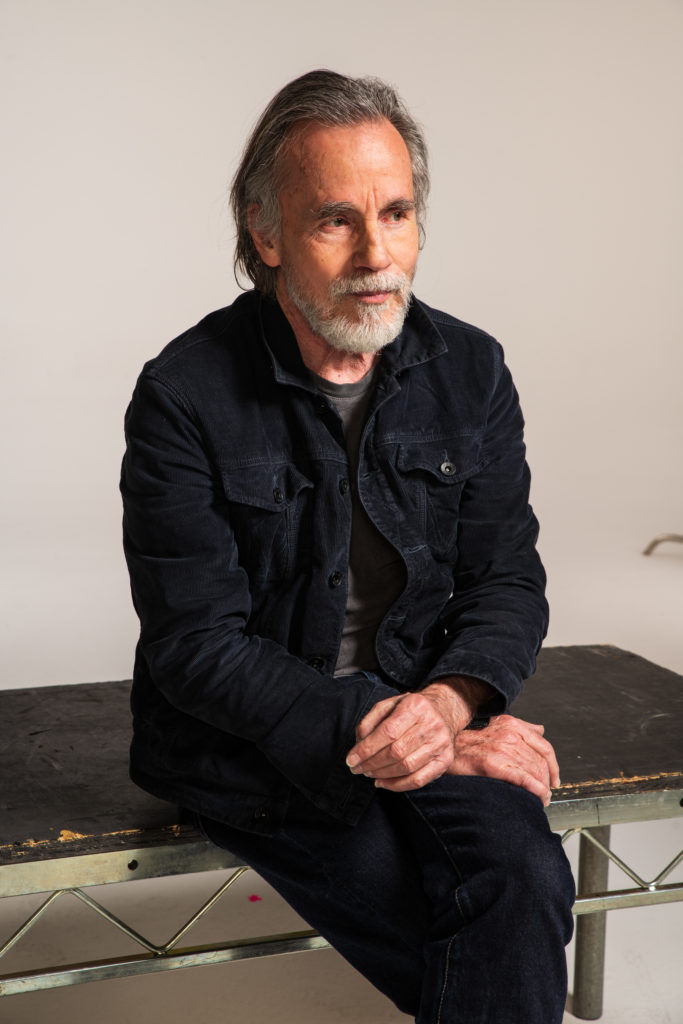

Since his 1972 debut album Jackson Browne, he has been hailed as one the Greatest Songwriters of All Time by Rolling Stone. Known for era-defining hits like “Running On Empty” and “The Pretender,” as well as personal ballads like “These Days,” Browne’s catalog has sold more than 18 million records in the United States alone. He’s an inductee in both the Rock and Roll and Songwriters Hall of Fame.

Throughout his 15 albums and over his storied career, Browne also regularly threaded activism into his life and songs, raising funds and awareness for social, political, and environmental efforts.

Downhill From Everywhere is Browne’s first new album in six years. Recorded at Groove Masters in Santa Monica, CA, it was produced by Browne, recorded and mixed by Kevin Smith. Mastering was by Gavin Lurssen and Rueben Cohen at Lurssen Mastering in Burbank, CA.

Downhill From Everywhere was cut with a core band that included guitarists Greg Leisz (Eric Clapton, Bill Frisell) and Val McCallum (Lucinda Williams, Sheryl Crow), bassist Bob Glaub (Linda Ronstadt, CSNY, John Fogerty), keyboardist Jeff Young (Sting, Shawn Colvin), and drummer Mauricio Lewak (Sugarland, Melissa Etheridge).

Downhill From Everywhere houses expressions of doubt, connection, purpose and longing, all while maintaining a defiant sense of optimism that seems tailor-made for these chaotic times. Browne explores environmental and socio-political themes: Human existence, clean air, fresh water, racial equity, democracy, and border concerns––topics he’s examined on occasion in his illustrious catalog.

The following Music Connection interview was recorded in May 2021.

Music Connection: I know many decades ago you wrote songs on piano or guitar, and the lyrics on some paper, or typewriter before computers. But on this new album, much of the writing process took place in the recording studio. Not demo to master steps.

Jackson Browne: To me, I am continually discovering that any number of things or any number of decisions are interesting and valid and you can pursue them. You just have to be open to what you are feeling and what you are hearing. It’s all trial and error for me. I don’t really have a dogma that I approach or adhere too. Keep your ears open.

Songwriting is a mysterious thing. Sometimes it feels a bit like consulting the oracle. As a songwriter, you want to catch people when they’re dreaming. You want to find a way into their psyche when they don’t see you coming. On the new album it changed a little bit. I write on a legal pad with a pencil. And at a certain point I used to write the whole song out line for line to see what I had.

What I found out a couple of albums ago was that it would be really great to see it typed. And I would be easier to see what was there instead of my terrible handwriting.

I read a lot, and to read it typed out double-spaced helps me see what the lyrics got. I rarely start writing out the song in a word processor until it is pretty much half written or if I got something. I use my phone now. The voice memo to my phone. And I sometimes put the voice memo on and record whatever. Not think about it. Then I’ll have a series of these voice memos that contain the search. “Right! Voice Memo 395.” I’ll write that. Let me figure it out. I didn’t start doing that until the last album.

As a matter of fact, the song I started to do that on was “Minutes to Downtown.” That was a song I started a few years ago. And when I started looking for the thing I was looking in the wrong year for this initial voice memo. There it was. One of the first voice memos on my phone.

I’ve actually written stuff that I’ve written one track at a time and shaped it. The long way around. From the beginning I used to use a cassette player. In the beginning I had cassettes I wrote with. After cassettes I started using Minidiscs, and they stopped making the damned MiniDiscs (Laughs). I have boxes. What I liked about the MiniDiscs was that they had ID’s. You could actually label things and go eight to them looking for a song. Now with the voice memo it is perfect for me.

MC: Tell me about working and bringing your songs to fruition with band members in the studio.

Browne: I rely on the players I’m playing with to uncover what is in the song. It’s always been that way. The music is informed by the way that everyone interacts with it in the room, and there’s this journey of exploring and cutting and re-cutting that can lead you to places you never would have ended up at on your own.

In the studio I very often record a song that is not finished. All the lyrics might not even be there. But I want to know what the song can do. Before I finish the lyrics. That happened a long time ago. I’d written a song by myself with a guitar in a room in Spain. And what you do to make a song finished with one instrument is develop the lyrics. So I get back to go play it with my band and I realize that I don’t want to hear a second verse I want to go right to a chorus. And I have to throw that verse away. And that changes everything about the song. But it’s clear that I don’t want to hear the band play two verses and then go to a chorus. I wish I had that information.

It goes back to “The Pretender” where I realized a song that I thought was finished was still malleable. I could make a change in the structure of the song not in the studio. To me, that was hair-raising at the time, because in those days it was more formal. The idea of calling a session on the people that you have there and the amount of time you had to work in and what you are paying them was more imposing.

In the case of “The Pretender,” Jeff Porcaro and Craig Doerge played something that meant I needed another line. I had a two-line phrase and if they did that it needed another vocal line. And Jon Landau, who was producing that record said, “This is great.”

They are doing this dynamic thing “but you know I’m gonna have to add another line…” Jon looked at me and laughed. “Well, you’re a writer.” It was easy. So much happens in the studio that it would be all right to go into the studio with a song that was not quite written.

MC: You have clear-sounding vocal performances on this new album. Did you change your diet? There is such clarity and direction, almost Indian guide-like precise vocals on the navigation.

Browne: [Laughs]. I don’t mind telling you, but I started working with an app from the wonderful singer Arnold McCuller [vocal trainer] who has worked with James Taylor for all the years. This app has given me a way to train my voice and listen to my voice. It’s a bunch of exercises.

When I first started, I could do it okay, a few simple sessions. And I’ve been doing that. I kind of came into my voice. I just kind of go ahead and learn how to sing at the end of my career. What the hell. (Laughs).

That experimenting with my voice and the palate was something that went on during the making of this new record. And that is as much a part of developing the songs as writing them. I’ve always done the best I can with what I’ve got. But I wish I had known at the beginning of my career how I could develop my voice. I’ve always tried to be a better singer, but that sometimes resulted in me trying too hard. If I listen to the way I sang on Late For The Sky that whole album I hold notes embarrassingly long. I sing too strongly at times when I could have sung something much quieter.

MC: Let’s further discuss Downhill From Everywhere.

Browne: What I think that this album comprises is a record of the search. Each case and each song represents an individual journey or subjects. “The Dreamer” I started writing many years ago and I had the music, but the subject of immigration was a hot button subject a long time ago. You had the vigilantism on the border. And I was gonna try and write about that. It could get very hard to try and tell the story. I thought I could sing about somebody who has a job here and a family there.

On “A Human Touch,” I started out wanting to talk about the conflict on the border, but the only way to talk about the conflict is to talk about the people living it, so it became about Lucina, a young woman Eugene and I both know. But the person who sees “enemies” everywhere is also a human being, and what I sing has to be true for that person, too, because I’m not talking about them, I’m talking to them. Even if they don’t like me singing about a girl who came to this country illegally, I want them to care about her.

On “A Human Touch,” I started out wanting to talk about the conflict on the border, but the only way to talk about the conflict is to talk about the people living it, so it became about Lucina, a young woman Eugene and I both know. But the person who sees “enemies” everywhere is also a human being, and what I sing has to be true for that person, too, because I’m not talking about them, I’m talking to them. Even if they don’t like me singing about a girl who came to this country illegally, I want them to care about her.

There are songs like “Love Is Love” and “A Human Touch” that represent embracing a subject more than finding a way of talking about it. All of these songs are in the present tense, which has not really happened in one of my records before. I realize they are an attempt to, in the present, come to terms with an issue that is important to me.

On the song “Downhill From Everywhere” I wanted the song to be a great track that you didn’t have to listen to or if you did, literally for five seconds, you’d get something from that, the juxtaposition of images. That represented a more cubist or abstract way of putting imagery together. Yet there is an overarching sense being made, hopefully. Each of these songs represents a search to uncover, to answer a question for myself.

There’s a deep current of inclusion running through this record. I think that idea of inclusion, of opening yourself up to people who are different from you, that’s the fundamental basis for any kind of understanding in this world.”

I think racial and economic and environmental justice is at the root of all the other issues we’re facing right now. Dignity and justice are the bedrock of everything that matters to us in this life. Then there is also the fact that there is the challenge we face as a country to try and solve the problems that have been with us since its conception. We’ve got a deep flaw in our DNA as a people that we have to address.

I see the writing on the wall. I know there’s only so much time left in my life. But I now have an amazing, beautiful grandson, and I feel more acutely than ever the responsibility to leave him a world that’s inhabitable.

MC: Los Angeles, California and Barcelona, Spain are central topics and perhaps at the core of this new work. Like “Minutes to Downtown” and “Song For Barcelona.”

Browne: Yes. I’d say Barcelona is a city that I really love and I inherited a kind of apartment there. It’s sort of a city that I grew to have a history with. I wrote the song part there and part in Los Angeles. I always assumed I was going to record it there. I even booked a studio and set a recording date and then I couldn’t go. Actually did that twice. And each time I had to cancel those plans and realized practically speaking I had to record it in L.A. But I also realized it was more appropriate to record it with my band because we all love Barcelona. It was more appropriate to be a person from California singing a tribute to Barcelona was going to be more value there. I have some really good friends in Barcelona.

“Minutes to Downtown” is a darker song, even when it comes in with a minor key. On the surface, it’s about living in Los Angeles, but it’s really a metaphor for life itself. I adore this city, but I’ve been trying to leave since around the time I finished my first album. You can love and appreciate and depend on a life as you know it, but deep down, you may also long for something else, even if you don’t know what it is.

MC: I want to ask you about Bob Dylan who definitely is in your DNA. Music Connection is displaying reflections and observations about Dylan from my archive celebrating his 80th birthday.

Browne: What Bob Dylan did for me, everybody and our generation, it will never have to be done again, you know. The way he opened up our thinking and our feeling and our view of the world only has to be done once. Maybe it’s done in other fields like film and painting and other art. As a people we’re constantly growing, expanding but the changes that Bob Dylan brought to rock & roll and songwriting are permanent. They’re part of us. People who are just being born into it now are being born into a world that wasn’t that way until Bob Dylan made it that way.

It’s a particular skill to write something in a few words that speaks volumes. It is very difficult to say how I feel and how I think about Bob Dylan in a few words.

MC: Guitarist Val McCallum. The weaving he does with bassist Bob Glaub and Greg Leisz is wonderful.

Browne: I’ve got some great players to work with. It’s pretty thrilling to work with someone like Greg Leisz. He’s a multi-instrumentalist and to decide with him what instrument he’ll play or talk about the register.

Val is unique. Very little words can do to describe what he does. He is the guy who is willing to go out on a limb and crash and burn. He is so thrilling and he plays something different every time, of course. What is going on between Val and Greg is amazing; they really listen to each other. It’s like they’re in duet.

They are over there on the same side of the stage, they play next to each other, so they really hear what the other is doing. And of course, they are playing the song, and I’m pretty much playing the same thing all the time. What varies with me is maybe the emotional charge or the degree, which I almost never change the melody or the phrase that I’m singing. They’re the ones that put this fresh music together each time a song is played. And they listen to each other intently and also crack each other up, because they both are so good. They support each other.

We go through and designate who is gonna solo on a particular place, but that’s only the beginning of the story. They wind up accompanying each other sonically in terms of register.

Sometimes with Greg, where I do shows and he is my only solo accompanist, sometimes we forget what different instrument he’s gonna play and we discover something in the song or just the tunings that he uses. It’s a very fertile environment to be playing in a band with these guys. I don’t know how to talk about music. I just notice the most fundamental things.

At one point we did a particular gig with this band and I hadn’t played with Bob in many years. And the combination of him and Mauricio Lewak was really distinct to me. Wow. He really changed what Mauricio was doing. Bob plays a particular way. I’ve done songs with Mauricio and we’ve cut them with some other drummer a few times. Or I called Jim Keltner, who took it to another place.

MC: You’ve worked with some terrific engineers over the decades, including Al Schmitt and Greg Ladanyi.

Browne: Early on I produced myself and worked with an engineer. They were rare occasions where I used a producer. Those were maybe learning experiences to work with someone whose job it is to chart a course and co-navigate a song. I don’t involve myself that much in the miking of drums. That’s an engineer’s job. And in some cases, what I’m deciding about is the register of an instrument or what goes on with the players.

MC: You have some scheduled tour dates for 2021. How do you select a concert repertoire or pick a set list? Does management make suggestions or does the playlist come from band members or even fan mail? You have this body of work, and there are obligations to play hits as well as deep catalog.

Browne: I should start by saying I’ve tried every which way and anyway you can possibly try it. I’ll give you an idea of some of the approaches. No set list. Or just call a song if you are playing by yourself or with one other person who knows your songs really well. And you can just say, “You know, we’re not really doing a set.” Or I’ll let the audience know early there is really no set list. I’ve done that for a while, and after a while my audiences are expected to call some songs, but you start to feel like a juke box, so maybe that is not the best way either.

I’ll say, for a long time, I thought I had to play all my new songs. I’d make an album and go out there and play, but I had a good friend tell me, “That is not a good idea. Some people are there to hear what they already love. You can’t just play them a bunch of new material. You gotta give them a chance.” And he said we [should] never play more than two new songs. Never. Think about it. That was Scott Thurston of [Tom Petty and] the Heartbreakers. That is a useful example to me. I love the Heartbreakers and when I’d go see them and they are playing songs from their entire body of work and those two new songs. And that was a very influential teaching moment. A learning moment for me from Scott.

Also, when it comes to picking, very often I’m not the best judge of how the songs go together. ‘Cause I think in terms of getting from one song.

The guy who is most helpful to me in that is Val McCullum. He is super- opinionated about what should come next and what should be included in the set and very like eager to interact with me and help plan the set in recent years. And he’s really right about a lot of things and trying stuff. It’s all intuitive, you know. What do you want to happen next? Not everybody cares.

It matters sometimes whether or not you can set up, getting from one instrument to the next. I’ve got to reach for this guitar, so I can’t do those two songs next to each other, putting a song in between. That’s a practical consideration. It does matter. Or I’ll be thinking stuff like I don’t want to do two songs with the same tempo back to back. It’s a mysterious thing. I enjoy getting everybody involved and everybody gives you feedback. If you do a particularly great set, “That one really works when we went from that song to that song.” It’s a band and everybody expresses an opinion about it.

MC: There is a different sonic aspect to your new album. I’d like to talk about some technical stuff.

Browne: Well, I’m the least technical guy. [Laughs].

I learned a lot this time; for instance, the search for the right mic. I had a really favorite microphone that was a Telefunken 251 that had been modified by Stephen Paul. This was in the past. He was always making these mics with super-thin diaphragm. I’d get this, but eventually something damaged it. It got a little perforation and the tiniest speck of a hole in it and suddenly it didn’t sound the same.

In engineering there is trust all the way down the line. The proof is what you can hear, you know. I learned a while back that I do know and can hear it all; I just don’t know what it is. When that mic got damaged, I got it fixed and it was very different. And then Stephen said, “I can put an EQ into your mic.” And I said, “Stephen, I don’t want an EQ,” and he replied, “Well, it has an EQ in it.” “Oh God, I didn’t know that…” You think everything has got some kind of response built into it.

So cut to the present, there was a mic he did at the same time. An AKG C-12 and it didn’t sound good with me. ‘Cause it sounded too bright, but I kept it because two other people who worked in the studio really liked it: Jennifer Warnes and David Crosby. They thought it was great and perfect for their voices. So I wasn’t always looking for a mic for me. When I couldn’t use the Telefunken 251 anymore, I tried that mic and suddenly that became my go-to mic. And what had happened was that my voice had changed. And the way I sang. I began working with exercises and stuff, and my voice suddenly sounded good with this microphone. And I thought, “Oh good.” That is still my go-to mic.

And in the middle of working on this record. Kevin Smith, who recorded and mixed the album, wanted to try something else. I think it was a Neumann U-47. I tried it and really didn’t think it was right. He said, “Sounds really good to me.” “Okay… Today we’ll sing on this mic and we will see what we get.” And my ears had to change to appreciate it, because I was always so addicted to the high end of the AKG C-12 that nothing else sounded right. It didn’t have the definition or presence. And the Neumann U-47 is a great mic. But I had to trust Kevin. He looked at me, “Yeah…This sounds good.” I’m laughing, “Okay. Go with it.”

Anyway, so I went through that kind of search, and on this record there are several different mics used. And in the end the mixing engineer is going to EQ the vocal the way it’s right with the track.

MC: What are your 2021 plans and projects in motion?

Browne: I’m working on a movie about drumming. I’m working as a producer with a director on a film about playing the drums. I’ve had the great fortune to play with some of the great drummers in rock & roll: Jim Keltner, Jim Gordon, Russ Kunkel, and Jeff Porcaro, so I appreciate them deeply. I don’t understand them, so I don’t really know that much about it. I rely on them but I don’t know exactly what I’d like to know. I’m a good sort of collaborator for a film on that subject, ‘cause I deeply want to know. That’s something that is quite a departure for me and a lot of new terrain.

And I have a love of traveling and hope to get back to Spain and to Haiti. And I want to go to places I’ve never been before. I hope we can get back to traveling safely. I really want to get back to work. There are plans for touring, which is a major thing, and to be able to play again.

Contact [email protected]

Jackson Browne will be on tour this summer and fall with James Taylor. Browne will also be doing some solo dates. For complete tour info, visit jacksonbrowne.com.

HARVEY KUBERNIK is the author of 19 books, including Canyon Of Dreams: The Magic And The Music Of Laurel Canyon and Turn Up The Radio! Rock, Pop and Roll In Los Angeles 1956-1972.

Sterling/Barnes and Noble in 2018 published Harvey and Kenneth Kubernik’s The Story Of The Band: From Big Pink To The Last Waltz. For October 2021 the duo has written a multi-narrative volume on Jimi Hendrix for the publisher.

In 2015 Palazzo Editions published Harvey’s Leonard Cohen: Everybody Knows, and Neil Young, Heart of Gold published in 2016. Otherworld Cottage Industries in 2020 published Harvey’s book, Docs That Rock, Music That Matters.

Kubernik’s writings are housed in book anthologies, most notably The Rolling Stone Book Of The Beats and Drinking With Bukowski.

Harvey wrote the liner note booklets to the CD re-releases of Carole King’s Tapestry, Allen Ginsberg’s Kaddish, Elvis Presley The ’68 Comeback Special and the Ramones’ End of the Century.

During 2020 Harvey Kubernik served as a Consultant on the two-part documentary television series Laurel Canyon: A Place in Time directed by Alison Ellwood. Harvey is working on a documentary about Rock and Roll Hall of Fame member singer-songwriter Del Shannon. Harvey was filmed for the documentary in production about Hollywood landmark Gold Star Recording Studio.