There’s a picture of me, when I was about six years old, sitting down to play the piano for the first time… I’m sitting on the bench with my dad, and I’m pointing eagerly at one of the keys. My dad has that expression of light impatience that he got whenever he was trying to teach me something and I wasn’t listening. There’s no music on the piano––just my dad, teaching me music, while I can’t wait to bang out some notes loudly and obnoxiously on this new object in front of me.

I had no idea, 14 years ago, what would result out of that moment. I had no idea that I would gravitate toward other instruments, learning five in total. I had no idea that I would end up playing shows in high school. I had no idea that, at 18 years old, I would last minute wind up wanting so badly to be a music major in college, instead of political science or education, like my parents wanted. It became so clear that music was what I was meant to do.

There was just one problem: I had to audition. I thought I was good to go. I thought I was as prepared as I could have been. Music is what I’m passionate about, so there’s no way they won’t let me in, my brain told me.

Guess what? I didn’t get in.

I was devastated. I wanted so badly to get in. I knew it was what I was meant to do, and I had flubbed it. I realized my problem wasn’t with my passion, it was in my practice. I had fallen off my habit of practice. I didn’t have any concrete strategies that I could fall back on and use to improve my playing, no matter what. I was lost. And I didn’t want myself, or any musician for that matter, to feel that way. So I set out to learn as much about practice as I could.

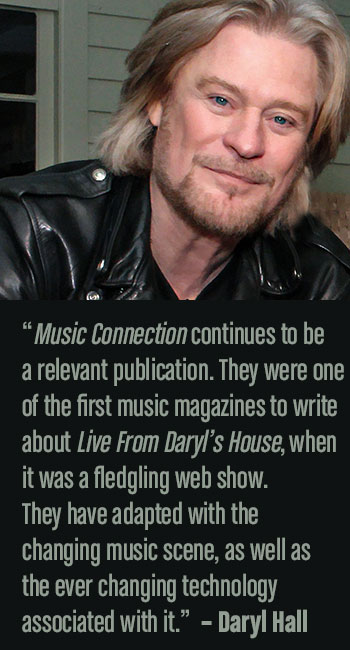

This article is the result of that effort––tips, straight from interviews with the pros, that will actually, practically help your practice. Simple, easy, and hopefully fun things that musicians can use anytime to help them. I interviewed two local musicians I’ve become connected with––Dr. Pete Madsen, professor of jazz studies at the University of Nebraska Omaha, and Nick Johnson, an active local educator, performer, and National Guard member who has played everything from cover bands to church to concert bands. I sat down with them and asked about their practice, how they work, and what has brought success. The result is a list of their helpful techniques, with a few of my own that I’ve picked up!

Apps

We have more access to technology than ever before. And the popular phrase “there’s an app for that” translates to music practice, too. There are numerous free and/or cheap apps available for both iPhone and Android that can aid your musical pursuits. I personally have a metronome app that I use every single day, as well as a tuner and UCLA’s music theory app, which allows you to practice reading sheet music, learning melodies, and identifying chords. Madsen highly recommends Tonal Energy, which allows you to record, tune, play to a metronome, and much more. He also recommends iReal Pro for jazz musicians, which allows you to practice to a pre-recorded backing track.

Exercise

Both musicians I interviewed emphasized the importance of daily exercise. It may not directly relate to anything musical, but keeping yourself in shape has been proven to keep you more focused for longer periods of time. For Johnson especially: “Daily exercise is important to me, especially on the military side of things. As a drummer, my practice is literally training my muscles to hit the drums. It’s important that I’m also training those muscles in other ways.” Madsen goes for a run “every day, as often as I can. You can’t keep your chops up when you’re playing a brass instrument if you’re not in shape.”

Breaking up time

Sometimes, we musicians are intense. We like to hole up in a practice room for hours upon hours in a row. However, a strategy that I’ve found (my two interviewees concur) is to break up your time instead of spending all of your energy at once. Madsen’s practice routine in doctoral school was made up of four hours a day, but it looked different: “I would practice for an hour, go for a run, practice for another hour, eat lunch,” and so on. Every hour of practice was met with an hour of doing something else, partially to keep from any physical burnout, but also mental burnout.

Record yourself

Recording yourself and listening back to it is one of the hardest things to do as a musician. It’s equivalent to listening to a recording of your own voice––“Do I really sound like that? However, the honesty of recording is a great tool for improvement, and now it’s easier than ever. iPhones have a built-in voice memos app that may not be the best quality, but will get the job done. I use it all the time. If you have more experience with recording technology, you can do what Johnson does, and record directly into software like Pro Tools. “I find it gives a performance aspect to my practice,” says Johnson. Plus, more advanced software gives you the ability to slow down the recording to hear exactly what you’re doing wrong.

Goal setting

Every week, on Sunday night, I sit down with my notebook and I write out my goals for the week. I usually organize them into different categories––homework, personal and practice. I’ve found that this is the best way to utilize my time wisely. Think of it like going to the gym: if you walk in, and have no idea what exercises you need to do, how likely is it that you’re going to actually work out that day, or have it be productive? It’s the same thing with practice. Even just writing down a few techniques in your planner every week can help. I’ve got to have a game plan for the week; otherwise, I’ll just end up noodling at the piano for an hour or two, without actually having improved at all.

Jamming

We’ve all been there: you sit down at your regular time to practice, you get prepared, you’re ready to shed, but as soon as you start playing, nothing seems to click. Although the natural tendency is to keep trying to play the things you need to work on (frustrating yourself in the process), try playing something you already know. Something you feel super-comfortable with that you can play while turning your overthinking brain off.

Johnson opens up every practice session by playing a song he already knows. It may not always be necessary for you to do this for every single practice session, but it can break you out of a funk and focus you up enough to get some work done. (Note: keep in mind that “jamming” and “practice” are different things entirely––only one actually develops and improves you as a musician.)

To combine two of these strategies, you can also break up your practice time with jams. Try practicing for 30 minutes to an hour, then jamming on a few songs, then another 30 minutes to an hour of practice. Getting other people together just for the love of music can help your practice, too. Madsen often likes to play in his church band, with people who are doing music not for a paycheck but because they love it. It can help bring a new perspective to his practice.

Find a new way to practice something old

For the longest time, the biggest struggle in my practice has been technical exercises. Scales, arpeggios, Hanon exercises, you name it. We all have to do them at some point. I personally hate it because it’s hard to focus on improving something when you don’t have to put in mental energy to do it. Most technical exercises are solely muscle memory. However, this can give you a unique advantage to make your practice time more exciting.

A trick I picked up in music school is listening or doing something else while you practice your technical exercises. For example, I have a friend who puts in headphones and watches Netflix while she runs scales. I personally love to put on podcasts and audiobooks while I do it. It doesn’t matter what you like or don’t like, the point is, scales and arpeggios can be much more exciting than we usually think!

If all else fails, there’s nothing wrong with taking a break

I can give you many tips and tricks to make your practice more meaningful and exciting, but at the end of the day, if you’re worried about burning out, there’s nothing wrong with taking a few hours or even a day to yourself. Depending on the day, and how much work I have to get done, I might take a few hours off but still work on music in some aspect, usually listening. If I’ve been really working hard and I’m feeling burnt out, then I’ll take a break from all music and do something else entirely to restart my brain. Everyone needs breaks, especially musicians, and taking a step back sometimes even helps me more in the long run.

When I do go back to the practice room, I’m more energized and excited than before.

Using these strategies, in some form or another, has changed my life. Practice isn’t what it used to be. It used to be routine, uneventful, unproductive, and boring. I never got where I wanted to go. That’s why my audition went so poorly. And to emphasize even more that you should use these strategies, after my original audition, I made a commitment to work hard. To develop my skills. After I made that commitment, I made it into music school. I accomplished what I knew I had to do. A couple of years in, and I’m more successful than I’ve ever been. The point is, if you’re passionate about music, or even just want to learn an instrument for fun, I hope that these practice strategies will be helpful to you. Anyone can learn music, it just takes the right methods, and maybe music will change your life, just like it changed mine.

REEVE JOHNSON is currently a Jazz Performance and English major at the University of Nebraska at Omaha. He is an active performer around Omaha and Lincoln, playing in several cover bands and jazz bands.